|

The Horse in Myth, Mystery and Magic Transcript From a talk by Jeremy James in Stuckeridge House, Devon March 23rd 2019

|

|

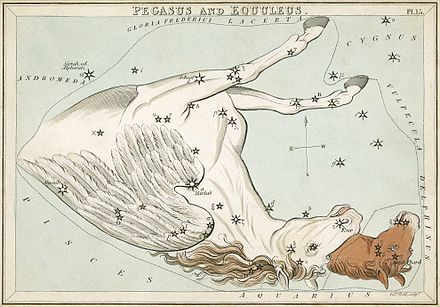

One hundred and eighty six light years from earth, in a constellation of the fourth magnitude, a pair of horses sparkle upside down in the darkness.

Together they sail through the stars to eternity.

Equuleus, the Little Horse, rises astronomically before Pegasus so is known as Equus Primus, the First Horse. He is depicted as a horse's head alone. He's named the First Horse for another reason too.

In the beginning of the world, the gods held a contest between them to decide whose gift would benefit mankind the most. Poseidon plunged his trident into the ground and delivered mankind of the first horse on Earth. His latin appellation in the heavens was to become Equuleus.

This elegant creature was immediately applauded by the gods. What a beautiful thing! They cried. How beautifully it moves! What a wonderful voice it has! What does it do? Poseidon revealed its tricks: its many gaits, it could be ridden, pull a plough, thresh grain.

Athena's offering was the olive: the gods laughed. Yet when she showed them of all its uses, the oil it produced, the abundance of its crop, how long it lived, the value of its wood, its celadon grey evergreen leaves, they changed their minds. To her went the prize.

The new, dazzling city was named after her. Athens, rather than Poseidon, whose beautiful gift remained to graze amongst the olives to remind man of the grace of the gods.

In time, the positions were to be reversed. The horse would prove to be the superior offering. His resourcefulness, his dexterity and many talents revealed him as Poseidon's masterstroke.

The horse soon proved himself to be of value to the mythologists: not least of all, he was dramatic to write about, in a way an olive is not. There was more of him to write about. He had a will of his own.

His role was to become defined as a divinely inspired instructor of mankind. The horse had begun his mythical journey. Having been delivered to the earth by a god, he held supernatural powers, one of which, granted to a select few, was the ability to fly. So entered the winged horse.

Winged horses do not fly: they float and glide. Pegasus is no exception. They are lighter than air, their flight is akin to angels. The take-off and alight directly from the ground, like a butterfly - or an angel - no fleshy weight binds them to the earth. Yet they are also solid. The ground they hover over and touch with their hooves - they never land in the way we understand - becomes sacred and magical.

When Pegasus floated down to earth and struck a rock on Mount Helicon with his hoof, the rock split, magically. Out poured sacred water, the water of inspiration. The Hippocrene Spring.

Whomsoever drinks physically - or metaphorically - from this spring will be inspired, Pegasus then became sacred to poets and to musicians. To both he gave metre and rhythm.

The muses of music are Polyhymnia and Euterpe. It's no co-incidence. Inspiration, metre and music, hoof and rhythm.

In some pieces of classical music the gait of a horse's hooves can be readily distinguished. Such a piece might be Schubert's Ballet in G Rosamunde, or more popular, Offenbach's Orpheus in the Underworld, also known as the Can-Can.

Orpheus in the Underworld was first performed on October 21st 1858. In this piece you can hear the change of gait clearly from trot to canter back to trot as you can if you listen to Schubert's Ballet in G or to Sibelius's Karelia Suite - which is clearly a hunt with horses in snow.

The rhythmic hoofbeat of horses gave rise to order in music. Had it not been for horses, we would not have had the music we have.

The cadence of his footfall brought symmetry to what formerly was shapeless, wandering and unmemorable. The steady, changing rhythm of his hoof brought structure. That structure composed itself into ordered, memorable music. You can hear the changing gait in very nearly every single piece ever written.

Hooves were the dominant sound of every day. They dominated and punctuated every piece of human commerce. Open your door and the first thing you'd hear in a town would be the beat of hooves. Anyone with a musical ear would have picked up its musicality and hummed or sung to it. It formed the foundation of folk music everywhere, and that was never written down nor formalised, relying instead on the beat of a hoof to keep the measure. The gaits provide endless, rhythmic variety.

When the internal combustion engine replaced horses on the streets, music lost its rapidly changing cadence and became instead, a beat: the beat of the steam engine at first and then of the internal combustion engine. When the melody of the horses' hooves grew silent, music would never be the same again.

So what's this got to do with Mythology? I hear you cry.

Everything.

The point of classical music is to take us away from the mundane, to expand and elevate the mind.

To lift us to a higher plane.

The myths are precisely the same, with the added advantage of being inspirational. Classical music is about appealing to the higher sense. Mythology is about attaining it.

The Hippocrene Spring is not just for the inspiration of poets: we may all drink from its magical waters and be inspired, transported and transformed. Inspirational music and mythology have the same effect. Myths are divinatory, they not only inspire, they elevate us and instruct.

Regard the following two myths.

The first is of Helios Apollo who was, or is, one of the Immortals: the god of the sun. The classicists pictured him in his blazing chariot driving his four celestial horses - PAPA by mnemonic - Pyrois, Aeos, Phlegon and Aethon - high into the sky. Up and up he climbed every day to the zenith of heaven before commencing the long afternoon descent - we all know how horses struggle with the downhill slope - down to the dazzling, Homeric wine-dark sea, to the Island of the Blessed. From there they pass beneath the earth to rise at Eos, Queen of Dawn's Golden Throne the following morning.

One day, in a moment of pride, Helios Apollo promised Phaethon, his mortal son, that he could have whatever he wished and swore by the Holy River Styx, which meant no part of his oath was retractable.

Phaethon asked to drive the celestial horses.

Helios Apollo at once saw his mistake. No mortal could drive the celestial horses. The horses were immensely powerful, they were made of flame, and besides the sky was filled with monsters: a vast lion, a huge crab, an immense goat, a huge scorpion, a great bull.

Undaunted, Phaethon took the reins.

Within a moment the horses were out of control: Phaethon was dashed from the chariot, the horses dropped from the sky and the earth was set on fire.

Phaethon was killed.

It took Helios Apollo all his strength to drive the horses back up into the sky. Each evening, the sky floods with Helios Apollo's fiery gold and red tears as he weeps over the rash promise he made on the fateful day that cost the life of his only son.

Every time you see a sunset from now on, you might remember this story. That the gold of a sunset are the tears of Helios Apollo. You might remember what it means. You might become the story teller - which is the purpose of a myth: to be conveyed.

So what does it mean?

On its most elementary level, it tells us not to make rash promises; we do not know how lethal the consequences might turn out to be.

On another, it teaches us not to attempt any enterprise for which we are wholly unprepared despite our enthusiasm, nor to wish for things that are beyond our control.

And yet, there is a twist in the tale. This is only half the story.

When Phaethon died, the Naiads, water nymphs, buried him beside the sacred river Eridanus which no mortal eyes have ever seen. They marked his tomb with the inscription:

Here lies Phaethon

Greatly did he Fail,

yet

Greatly did he Dare.

At once the story is inverted. Brave Phaethon! We too, will dare. And when we dare, we shall dare greatly. If we fail, we fall, but we cannot succeed unless we dare and if we dare, we might win and if we win, then ours is the sky and all the starry heavens.

Into this soars the second myth, of Pegasus and Bellerophon. Pegasus the untameable winged horse. No mortal hand had been upon him.

Bellerophon, a mortal, spotted this horse as soon as he alighted upon the earth and a plan immediately presented itself. He needed this flying horse to achieve it. His plan had two parts: first to control the horse and the second to achieve the bigger plan. He did something that none of us have ever done.

He enlisted the help of the goddess, Minerva.

She supplied him with a magic bridle.

Bellerophon began his schooling of this lighter-than-air horse. Soon, he had mastered him.

Now came the main part of his plan.

To slay the unslayable Chimera. The monster who had ravaged the land for as long anyone could remember. He ate women, murdered children, destroyed crops, tore down houses.

No, the people cried, it could not be done. The Chimera was too big, too terrible to confront. Bellerophon and the horse would be killed, mortal or immortal. They had no chance.

How often have you heard the naysayers?

Bellerophon ignored them. He dared. Shouldering his bow and quiver of arrows he girded on his sword. Vaulting up onto Pegasus, away they blew. Don't! Everyone cried! You cannot succeed! You will die in the attempt!

Circling the snapping Chimera, Bellerophon steadied his aim, down flew Pegasus straight toward the flailing beast.

Bellerophon drew his bow. The arrow flew. With a single, perfect shot, the Chimera was blinded. Leaping off Pegasus he finished him off with a spear. Not only did he slay the Chimera but saved the entire land by his valiant and selfless act.

So what does this story tell us?

It tells us to Have A Plan. Without a plan we go nowhere. Achieve nothing. We stagnate. We need a plan. All of us. And within that plan, we need an even greater plan, to benefit more than ourselves. Then to strike out, regardless of what anyone says.

When we put these two myths together, their full impact is translated to us. We shall take that leap of faith and trust that the gods themselves will be at our shoulder.

We shall mount our own horse, he'll take wing and we shall overcome the most trenchant obstacle. We too shall slay the unslayable Chimera on a Pegasus of our very own. The more selfless our purpose, the more successful we shall be.

These myths are not just stories. They form part of our culture and of our spiritual and intellectual inheritance. They are the educatio of the soul. When we inhabit them, they inhabit us. They elevate us. When we interpret them properly, we ensure that all our actions and thoughts are delivered not just for ourselves alone but for the wellbeing of our fellow human, animal and of the earth itself.

We all know the story of the Fall of Troy. Troy was not just a town, it was the city of God, its fall a catastrophe. Here the horse was central to its demise. He is the most memorable figure in the story. Everyone knows the Trojan Horse. Whose side was he on? Man's? Or the gods'?

Or is he the mystical bond, the union between man and deity? Which is his true mythological role.

In modern parlance he's our subconscious bringing to fruit our deeper desires. Yet our deeper desires are not always what we expect.

In the Greek world the horse was adopted as the favourite of both the gods and man. Why? Partly because he is not the most submissive of animals. Even when fully in-hand there remains something unpredictable and wild about him. He is not to be owned or possessed. He reflects our duplicitous desires. Both considered and wayward at the same time.

To the Norseman he is as the eight legged mystery horse of the one eyed Odin, galloping through the the mists of the mind, Odin having given one eye in return for wisdom.

Sleipnir is of divine origin in Nordic tradition, quite set apart from the Greek. If you do what goes against your conscience, you offend The Law - both spiritual and temporal. And Sleipnir will find you out.

In the story of St George and the Dragon, the horse is the emblem of steadfastness and right.

St George is usually painted upon a white horse though I know of a church in Georgia where he's mounted on a black one. St George in this instance is an ancestral figure, a chthonic divinity.

Incidentally, the lady in the St George

paintings is there because she was the sacrifice. Many having been sacrificed

before her. She is saved in the nick of time although it takes him three days to

do so.

You'll see remnants of broken lances on the ground in other oils too. He had a real fight on his hands.

St George symbolises our own battle with our own demons. All we need is a good horse. This union of man, God and horse introduces 'Holy Chivalry', the perfect way to be The Perfect Knight, that Chaucer wrote about.

Chivalry denotes a code of conduct.

It was brought to prominence through the writings of Chrétien de Troyes, a French poet and trouvère, or troubador. Our own Arthuriad, the knights of the Round Table form the basis of these legends. The Quest for the Holy Grail. Strict vows of obedience to the Code were sworn by knights, extending well into the late Elizabethan period.

These stories metamorphosed into searches for the truth of all truths: Christ as The Knight. The Crown of Thorns becomes a helmet. The truth is a sword. Onward Christian soldiers marching as to war. We've all sung it. There's also the legend of Helen of the Cross having found the three nails of the crucifixion: one she kept, one she gave to Constantine to wear in his crown and the other became part of the bridle of a horse. It's referred to in Zacharia in the Old Testament - or rather there is an oblique reference to it as a prophecy.

Horses were not just part of but central to this mythology. Once again they are perceived as the divinely appointed animus, the spirit guide occupying the space between man and Godhead. And then later, in the following 'myth.'

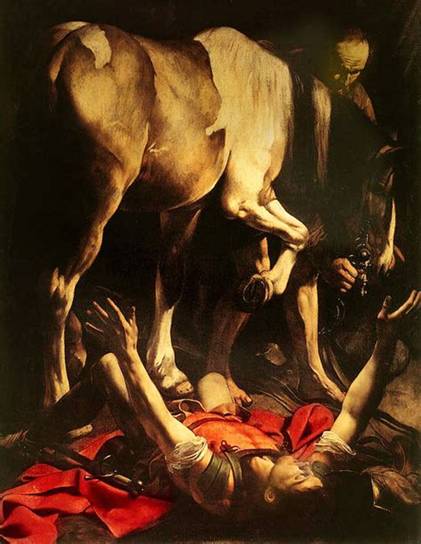

In Caravaggio's painting of the stricken St. Paul, although not strictly a myth, it comes close through Caravaggio's deft hand.

The blinded St Paul lies beneath the hooves of a padnag. A common, rent horse. St Paul has been thrown. Physically as well as spiritually. To be thrown from a high mettled horse was regarded as poor horsemanship but acceptable. To be thrown from a rent horse, a padnag is outright humility.

Caravaggio has made the horse play his

role as the instrument of the justice of God. The proud will be humbled, blinded

and brought to their knees - or in this case, laid flat out on his back.

In the Biblical story there is no horse. Caravaggio painted in the horse in full knowledge of his power as a mythological symbol. He stands above St Paul. Does he recognise what's happened? Or doesn't he care? He already resides in mystic unity with God. The man flat on his back has nothing to do with him.

Even though he's just a padnag, he's retains his dignity. He is above the fallen man. His nobility is intact. Take the horse out of the painting and it loses all its power, its reference. The horse adds dimension. Just as he did to music.

When they took the horse out of music the nobility in the music was lost. When you take horses out of politics, (that is to say, the real Knights of politics) you take the nobility out of government.

The horse represents the very essence of the high mind, the upright life. Eudaimonia: he is it personified. He seeks no wealth, no recognition, no place, no starring role. He knows only truth, he cannot lie. He is always in the present, he bows to no god, he lives a clean, exemplary life. All he seeks is to be himself, have his food and water.

By not seeking to be looked at, he stands acclaimed.

Don Quixote was prepared to ride into hell for a heavenly cause. Even though his horse, Rocinate is described as a broken old jade, in spite of it and of Don Quixote's eccentricities, we admire them both for their endurance. I don't think Cervantes was mocking his mad old knight at all. What he was saying was look at what we have lost.

The pure knight upon his horse is the living essence of the Tao, the flow of the universe, The Path.

Russia gives us The Glass Horse, Guardian of the Soul of the World, whose muscles screech as he moves and sharpens his hooves on the ice. He's a terrifying creature of the frozen wastes. He's also the symbol of perfect natural order. In the same legend, wolves are Guardians of the Heart of the World. The symbolism of the fragility yet the power of the horse is made complete by his glassy form.

The magical himori, The Wind Horse of the Altai and the taiga is not to be approached: there he stands, a horse skull nailed on the end of a fallen tree trunk, its limbs becoming his twisted wooden limbs. His rider is clothed in rags. His head is the skull of an antlered stag. He is the spirit of the trees, the earth, haunter of forests, you do not touch a himori. You bow, tie a ribbon to him and move on, crossing yourself that he leave you with a blessing and not a curse, only you will know which you deserve and you will pay. They have power. Stumble across one and I defy you not to feel it.

Then comes the mystery horse.

The Seian Horse is Mystery Horse. He's tricky: you really do not want to conjure him up. He's the horse of possession, he possesses the possessive. Of jealousy, of greed, of passions, he's bad luck. He has slain all who possess him or rather, who have been possessed by him.

He definitely plays to his own rules and slays far more than he mends.

The Seian Horse afflicts us. He is an affliction. It's hard to know if we invite him in or he comes of his own volition or even if he springs from some pre-conditioned, pre-determined matter that hovers in our DNA. He's Master of Possessiveness, its King. He infests the heart with jealousy - particularly between man and woman. He's destructive, horse of ill fortune. Anyone who has experienced his presence knows he's hard to get rid of, he hangs about, waiting to spring his trap and destroy. Yet, oddly, he does good. In his perverse way he can bring us to our senses if we defy ourselves, challenge our beliefs and in the act of defiance, change.

We do not accuse. We have no right. We do not judge. Are we so perfect ourselves? Point a finger at your peril. You will be the loser. The Seian Horse will come for you. The Seian Horse shows no mercy.

You won't find much written about the Seian Horse, no one dares to invoke this hard judging demon. I've written his story too, I'll get it published one of these days, if any publisher be so brave, he's very bad luck to have about, yet you can befriend him. If you do what he says which is the reverse of what tortures your heart, he will set you free. Through him we are forced to unlock our most stubborn assertions, the very ones that bring us the greatest pain, and through that sacrifice, we shall be set free. He's a bitter master. Yet he is just. He is what he is. He's the immortal corrective equi-demiurge. He springs from peculiar blood and peculiar blood he stirs. Beware the Seian Horse, he's closer than you think.

Many people believe their own horses to be connected to a Higher Power of some sort, with whom they share a soul in common. My horse knows me inside out, you hear someone say. He knows what I'm thinking. He does what I want to do before even I know it. The horse dies and something in the owner dies with him. Mark the mausolea the Romans put up to their horses. The epitaphs written, poetry versified. The heart of Lombard, the horse of Sir Giles de Berkeley who carried him to Jerusalem and back, lies beside him in Cobberly Church in Gloucestershire.

Horse and owner become linked beyond the grave.

Thousands of horse bones lie entombed with their patriarch.

Statues, carvings, paintings, images, locks of mane and tail lie in little boxes and cupboards all across the world, my house is full of them.

No lesser authority than Xenophon said it: there exists a spiritual bond between a rider and his horse.

And what of the horse? We will not lay stripes on these Roman citizens, they may not take their revenge in this life but they will in the next.

Some horses will not let anyone else but their owner ride them - then the horse knows. It's monogamous. Purity again. The undefiled. The horse will not be so lightly tempted. He will stand his ground, like Lars Porcena, he will defend the bridge, his right. You shall not pass.

The neighing of a horse has meaning: on the death of King Smerdis of Persia, claimants for the throne stepped forward on their horses. It was decided that whoever's horse neighed first would be the next King of the Persian Empire. Darius's stallion spoke first. To the Persians, the voice of the horse was the spoken Will of God.

Water horses - Kelpies - are haunters of river banks and of streams, they lure men to a watery demise. They're usually depicted as half-naked women lolling about on rocks, enticing the odd itinerant male to pass the time of day.

Coltpixies are the eerie horse of quagmires who summon the mortal horse into the quicksand to become the living dead - the Liminal horse: these terrorised travellers in the Middle Ages. There was a lot of undrained land, horses foundered. It's not a joke. There's one on Claerwen top in Wales. He took my three horses down into one. They take the weight of a pony, not a horse. All those living on moors will know all about them.

Fire horses - if you were born in either 1954, 1966, 1978, 1990, 2002 then you're a Fire Horse in Chinese astrology. You're hot-blooded. You can change direction at full gallop, you incline to lay your ears flat and bite without provocation, you're wild at heart and prefer the company of your own kind. You make enemies as fast as you make friends. Watch out though for them, they set fire to the earth, they're nearly as dangerous as dragons. We love them.

Sun horses are fire horses. St George and the Dragon again, representative of the Sun Horse, of light.

Celestial horses are true fire horses.

Earth horses are magical horses. Horses have been used extensively in magic for cult practices. You might recall the attacks on mares a few years ago - these were demonic cults all tied up with the mare ridden by the Night Hag. They have unpleasant resonances with witch power particularly over women.

The Night Mare presages terror, the incubus, marë or mara: old Saxon. The incubus straddles its victim's chest at night and locks them metaphysical torpor. Also called the Night Hag, the riding of the Witch. It's troublesome to horses, its symptom is the knotted mane - counteracted by hanging a stone with a hole in it over the stable door. This stone is not man made, it's naturally occurring and are regarded as sacred. Don't walk past if you see one. Pick it up. It's invaluable.

It's been called the Pan stone. It thwarts the marë, the witch of night and the devil who steals into the stable and gallops the horse to hell and back to leave her sweating, terrorised with a knotted mane, it's an alarming spectacle. I recall a mare in Sussex in 1970 odd, finding her in the early morning in a terrorised state. She had a knotted mane, was white with sweat, panting and wild-eyed. We had to move her not just from her stable but to another farm entirely. She took weeks and weeks to recover. We had to cut off her mane, we could not untangle it.

Horse brasses were employed as charms to protect them from the mare.

It was termed Facinatus by the Romans - the evil eye. Still found all over the Middle East and Turkey, I've met plenty of horses with them, mine wore them. In fact all my horses have worn them. The Nazar Bonçuk. It's very old, to be found in the writing of classical antiquity, Plutarch wrote about the evil eye two millennia ago, how the rays that come from the evil eye have the power to create the destructive energy of envy, which leads to sickness of body, spirit and mind. It will destroy a horse, so claimed the ancients.

The Marie Llwyd is a Welsh tradition to dress up in a sheet with a horse skull on your head and go about first steeping people on New Year's Eve. It brings good fortune, even though the spectacle is alarming.

A skull conveys the idea of a lost presence though materially still apparent. It has latent power, impelled by the spiritual realm. A connection between life and earth. The Liminal Horse again, although the Marie Llwyd also represents the rider.

Generally, a horse skull brings luck and repels evil. Skulls placed under floors were used to create an echo in music rooms - and in churches since loud noises were believed to expel evil. The latent spirit derived from the skull has shamanistic resonance. Hence the himori.

Marocco the Magical Horse was the most famous horse of the late Tudor and early Stuart period in England. Shakespeare wrote about him, Francis Bacon, Walter Raleigh, Kenelm Digby, John Donne and half a dozen others. He performed magical tricks. Thrice indicted for witchcraft and thrice released his schooling was celebrated by Gervase Markham in Cavalrice and was to become the foundation mark for natural horsemanship. He's not a true magic horse, but he's close. People believed he was possessed of supernatural powers weaving between witchcraft and trickery.

Talismans - some are natural, some man made: colour is a natural talisman, so are whorls, stars, white marks, solid colours - there's a whole language about them. Whorl of the spurs, whorl of wealth, mane of ill fortune, the swinging tail - horse of a rake who's loved by all yet hates himself.

To conclude, we are bound to admit that Poseidon's gift to mankind has become far more than the gods envisaged. He's long outstripped Athena's humble olive.

Not only has the horse become our companion, filled our lives with legends and stories and given us cadence in music, he's inspired it with beauty. Horse motifs decorate the world around us from statuary to artefacts. Many stone built stables are very fine. All high fashion has historically been equine related. Why? Practicality, necessity and style. It has brought panache.

Good posture is related to a good riding seat. Courtliness, manners, decency all spring from chivalry which is derived from horses. Fashion these days is execrable. Why? There's no horse in it. No dignity. No nobility. Today's fashion, at least for men, is the dullest there has ever been.

The horse stands not as sentinel, but side by side, shoulder to shoulder alongside man in his evolution. He stands at the gates of our kingdom in heroic posture. There's not a place man has gone his horse has not gone with him - he's won our wars, put kings on the throne, carried our munitions and posed for our art. He's drawn our ploughs and borne our burdens. He'll be in space in a minute - he's in the next Star Wars movie for sure.

And yet, we know nothing of his heart. Have one horse and you have a friend. Have two and they retreat into their own inscrutable society. They keep their mystery to themselves. We regard them, ponder over them, think about them, but how many of us ask what they think of us? What lies behind those eyes? What measure of time and patience, what measure of the divine?

They inhabit the uncorrupted land. Think the incorruptible thought.

After spending a year in the land of the Houyhnhynms, Gulliver tells us he 'contracted such a love and veneration for the inhabitants that I entered on a firm resolution never to return to human kind, but to pass the rest of my life among these admirable Houyhnhnms in the contemplation and practice of every virtue, where I could have no example or incitement to vice.' Their manners, customs, habits and philosophies, he found, outstripped our own. To them, a lie was unheard of: they didn't even have a word for it: they epitomised Eudaimonia.

Which state occasion is not instantly lifted by horses' presence? The minute they appear, everything rises. Why is this? It's in his essence: it's to do with nobility, I keep saying it. I keep saying it because it's true. He affects us morally. Physically. Mentally. Mind, body and spirit. Anything to do with horses elevates us, and that, to me, is their myth, that, their mystery and that, their magic.

Note:

On Originality

'Flaxman says truly one may collect too many materials and authorities, and habituate oneself to rely too little on one's own resources. He accuses the French of this. He was pleased with my quotation 'as you like it,' '"Base Authority from Books." When I told him how much his originality had been copied and appreciated he said they would do well to seek those beauties as I have done in the works of God.' C.R.Cockerell on John Flaxman.

Books referenced:

| Borrow. G., | The Romany Rye, | Dent, (1914). |

| Brown, T. | Tertullian and Horse-Cults in Britain. | (1950). |

| Cooper, J. C. | Dictionary of Symbolic and Mythological Animals. | Thorson’s, London. (1992). |

| Corkhill, W. H. | Horse Cults in Britain. | (1950). |

| Cunliffe, B. | Pits, Preconceptions and Propitiation in the British Iron Age. | Oxford Journal of Archaeology. 11 (1). (1992). |

| Dearborn, F. et al. (eds). | Encyclopaedia of Indo-European Culture. | (1997). |

| Frazer, J. G. | The Golden Bough. | New York. (1922). |

| Garwood, P. et al (eds). | Sacred and profane: Archaeology, Ritual and Religion. | Oxford Committee for Archaeology. (1991). |

| Gelling, P. & Davidson, H. E. | The Chariot of the Sun. | J. M. Dent, London. (1969). |

| Grant, A. | Economic or Symbolic.In: | |

| Graves. R., | The White Goddess. | Faber and Faber. London. (1997). |

| Green, M. | Animals in Celtic Life and Myth. | London. (1992). |

| Guerber. H.A., | The Myths of Greece and Rome. | Harrap and Co. London. (1913) |

| Howey. M.O., | The Horse in Magic and Myth, | Rider, London (1923). |

| Mallory, J. | The Ritual Treatment of the Horse in early Kurgan Tradition. | J. of Indo-European Studies. 9 (205-11). (1981) |

| Massey, G. | The Natural Genesis. 1883. | New York. Samuel Weiser. (1974) |

| Merrifield, R. | The Archaeology of Ritual and Magic. | Batsford, UK. (1987). |

| Moore-Colyer, R. J. | On the Ritual Burial of Horses in Britain. (1993-94). (1994). | |

| Philpott, R. | Burial Practice in Roman Britain, | BAR British Series. 219 (198-205). (1991). |

| Piggott, S. | Heads and Hoofs. | Antiquity. XXXVI. (1962). |

| Redgrove. P., | The Black Goddess and the Sixth Sense. | Paladin Grafton Books, (1989) |

| Tooke. A.M., | The Pantheon, representing the Fabulous Histories of the Heathen Gods and Most Illustrious Heroes. | Longman & Co. (1824). |

.Home